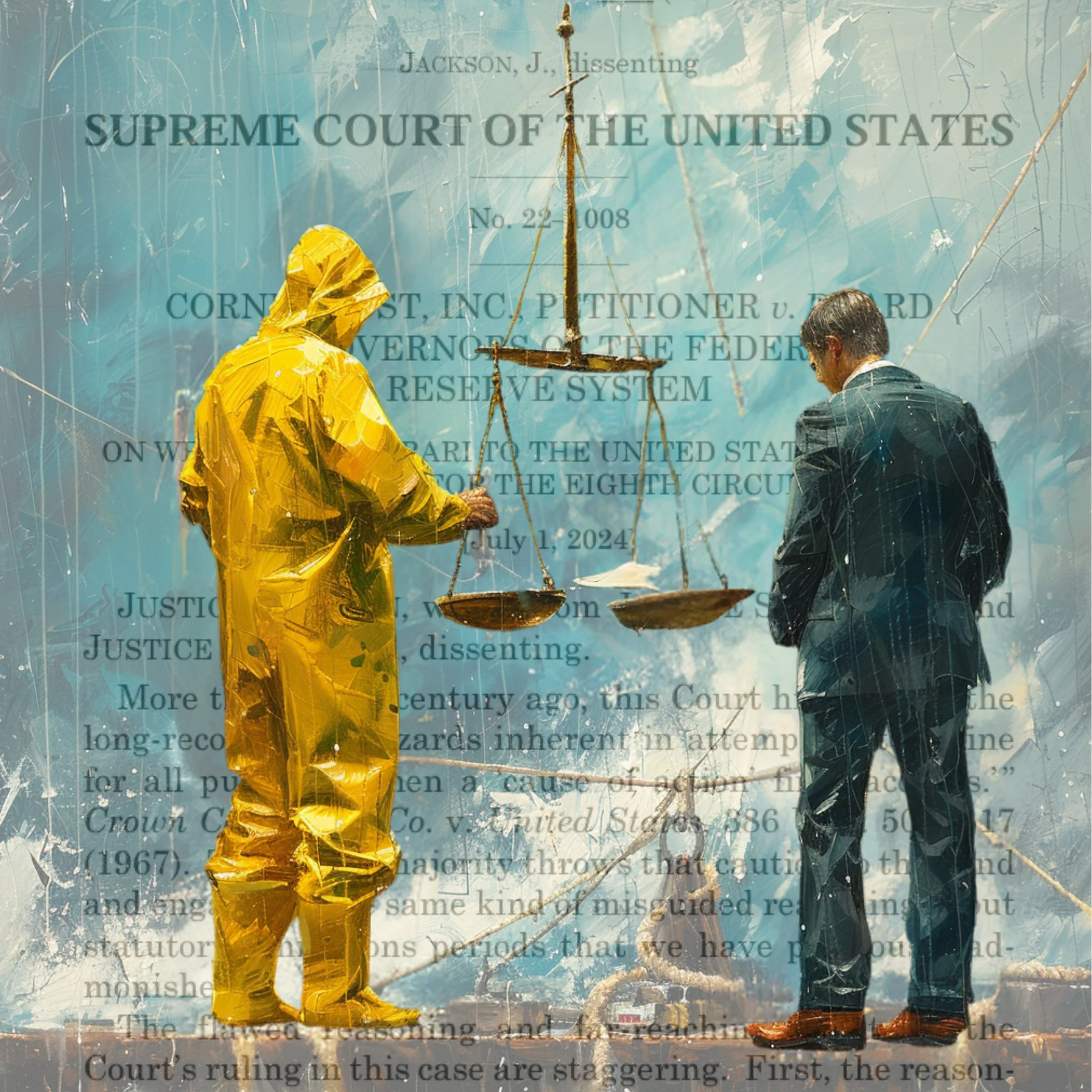

Is a Regulatory Storm A-Brewing?

Is a Regulatory Challenge Storm A-Brewing?

Will the Corner Post decision, particularly in light of the Supreme Court overturning the Chevron deference doctrine, invite the manipulation and gamesmanship the Dissent warns of?

On July 1, 2024, the Supreme Court delivered its opinion in the Corner Post, Inc. v Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System case. Factually, this case involved credit card related fees, but the issue before the Court focused on the statute of limitations applicable to challenging an agency’s rulemaking and when a claim “accrues” for purposes of a plaintiff bringing a case. Historically, courts have treated the 6-year applicable statute of limitations for challenging an agency rulemaking as running from the publication of the regulation. Today, the court rejected that view and held that: “An APA claim does not accrue for purposes of §2401(a)’s 6-year statute of limitations until the plaintiff is injured by final agency action.”

The Corner Post decision follows the Court’s recent decision overturning the Chevron deference doctrine, under which the courts previously granted deference to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of ambiguous statutes. So what does this mean? Justice Jackson, writing for the dissent points to the procedural history of the Corner Post case, highlighting that Corner Post, Inc. was not initially a plaintiff and only added in order to survive a statute of limitations challenge. Justice Jackson asserts that the Court’s holding is not only wrong, it invites gamesmanship and manipulation.

From the Dissent (Jackson, joined by Sotomayor and Kagan):

“Thus, even before I analyze the statute of limitations arguments, one can see that this case is the poster child for the type of manipulation that the majority now invites— new groups being brought in (or created) just to do an end run around the statute of limitations.1 To repeat: The claims in Corner Post’s lawsuit were not new or in any way distinct (even in wording) from the pre-existing and untimely claims of the trade organizations that had been around for decades.…

….But here we are. Three-quarters of a century after Congress enacted the APA, a majority of this Court rejects the consensus view that, for facial challenges to agency rules, the statutory 6-year limitations period runs from the publication of the rule. Instead, it holds that an APA claim accrues “when the plaintiff is injured by final agency action.” Ante, at 1. The majority maintains that the text of §2401(a) demands this result. But if that answer is so obvious, one wonders why no court proclaimed it until more than 75 years after all the statutory pieces were in place. To explain how the majority got this ruling wrong, I find it necessary to provide the right answer….

…For many kinds of legal claims, accrual is plaintiff specific because the claims themselves are plaintiff specific. But facial administrative-law claims are not. This means that, in the administrative-law context, the limitations period begins not when a plaintiff is injured, but when a rule is finalized….

…In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 603 U. S. ___ (2024), for example, the Court has reneged on a blackletter rule of administrative law that had been foundational for the last four decades. Id., at ___ (slip op., at 30). Under that prior interpretive doctrine, courts deferred to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes that Congress authorized the agency to administer. Now, every legal claim conceived of in those last four decades—and before—can possibly be brought before courts newly unleashed from the constraints of any such deference. See Tr. of Oral Arg. 74 (Assistant to the Solicitor General explaining that this result “would magnify the effect of” overruling Chevron)”

The majority largely dismissed the dissent’s concern regarding an influx of unnecessary litigation and plaintiff gamesmanship. The majority stated that many major regulations are challenged during the first six years and the resulting court cases would set precedent or persuasive authority. If no such authority existed, then the majority indicates that cases by proper plaintiffs can, and even should, be brought. The majority calls to Congress to make any desired changes to the Administrative Procedure Act if congressional intent was to have the 6-year statute of limitations run from publication of the regulation.

From the Opinion of the Court:

“Given that major regulations are typically challenged immediately, courts entertaining later challenges often will be able to rely on binding Supreme Court or circuit precedent. If neither this Court nor the relevant court of appeals has weighed in, a court may be able to look to other circuits for persuasive authority. And if no other authority upholding the agency action is persuasive, the court may have more work to do, but there is all the more reason for it to consider the merits of the newcomer’s challenge….

…Perhaps the dissent believes that the Code of Federal Regulations is full of substantively illegal regulations vulnerable to meritorious challenges; or perhaps it believes that meritless challenges will flood federal courts that are too incompetent to reject them. We have more confidence in both the Executive Branch and the Judiciary. But we do agree with the dissent on one point: “‘[T]he ball is in Congress’ court.’”